Artist Wendy Klemperer went to college for science, but then realized she wanted to be an artist. Luckily, her biology knowledge came in handy during art school.

When was the last time you discovered a surprising connection between two different subjects in school like science and art or history and gym?

Both of Wendy Klemperer’s parents received advanced STEM degrees from Ivy League schools. And Klemperer herself graduated from Harvard, with a degree in biochemistry. But she doesn’t spend her days in a lab or presenting research in elite institutions. Instead, she digs around scrap yards and construction sites for unwanted pieces of metal.

Klemperer is a professional sculptor who uses metal to sculpt animals in motion. Most of her work features rebar — steel rods that are often used in construction to reinforce concrete. Her creations vary from porcupines with realistic-looking spines to birds with sheet metal for feathers, to muscular, prowling felines.

As we mentioned, Wendy grew up in a scientific household. Not only were both of her parents scientists, but they encouraged her to excel in STEM academically. Although she liked math throughout elementary and middle school, she struggled with it in high school. Since her parents would not let her drop the subject, they would sometimes stay up until one in the morning together to figure out her math homework.

Animals enthralled Wendy ever since she was a child. She thought that she might become a veterinarian or animal behaviorist along the lines of Jane Goodall or David Attenborough.

Still Klemperer wasn’t entirely sure what she wanted to study when she got to college since her interests ranged from science to art to reading, in addition to her fascination with animals. Furthermore, she didn’t even get into Harvard the first time she applied. So she attended the University of Rochester on her parents’ suggestion, partly because it had a good chemistry department. While there, Klemperer took both a science and an art class each semester since her parents required her to take science classes despite her love of art.

Even with this balance, she struggled in her STEM classes. At one point, one of her math professors encouraged her to drop the class because she was doing so poorly. Her mother, however, convinced her to take the class in the off semester. Fortunately, this meant that the class size dropped from 200 students to 20. The smaller class size helped Klemperer to focus and eventually excel. This experience taught her that if she worked hard and didn’t get discouraged, she would succeed. Her grades in her math and chemistry classes rose, and she enjoyed her organic chemistry class despite the fact that it was known on campus for being extremely difficult.

After her sophomore year at the University of Rochester, Klemperer transferred to Harvard, where she continued to take both STEM and art classes.

One semester, she tried to get into a painting class but it was full, so she registered for a sculpting class. She “absolutely fell in love” with sculpture. The professor explained the creative process in a dynamic way, developing ideas through drawing, making models, and eventually sculpting in a variety of media.

She majored in biochemistry at Harvard, where her classes often had as many as 500 students in them. Biochemistry is the study of the chemicals that exist in living organisms. Living organisms are primarily made of molecules involving carbon. Molecules are atoms that are bonded together, like the two hydrogens and one oxygen atom which combine to form one water molecule.

Because life on Earth depends on carbon, most biochemistry focuses on organic chemistry, which is the study of molecules that contain at least one carbon molecule. Though these classes were challenging, Klemperer enjoyed learning about and visualizing processes, such as how carbon atoms form hexagons or chains as they bond with other atoms, how the double helix of DNA replicates, and how proteins fold.

Gradually, Klemperer’s passion for art dominated. After graduating from Harvard, she attended Pratt Institute, one of the best art schools in the world, and received her bachelor’s in sculpture. Although she experimented with figuration and abstraction when she started at Pratt, she found herself drawn more and more to animal imagery. For her, animals are no less interesting than people: “…the animal realm seems no less important to me than of humans.” She values “observing the continuity between all forms of life on earth.”

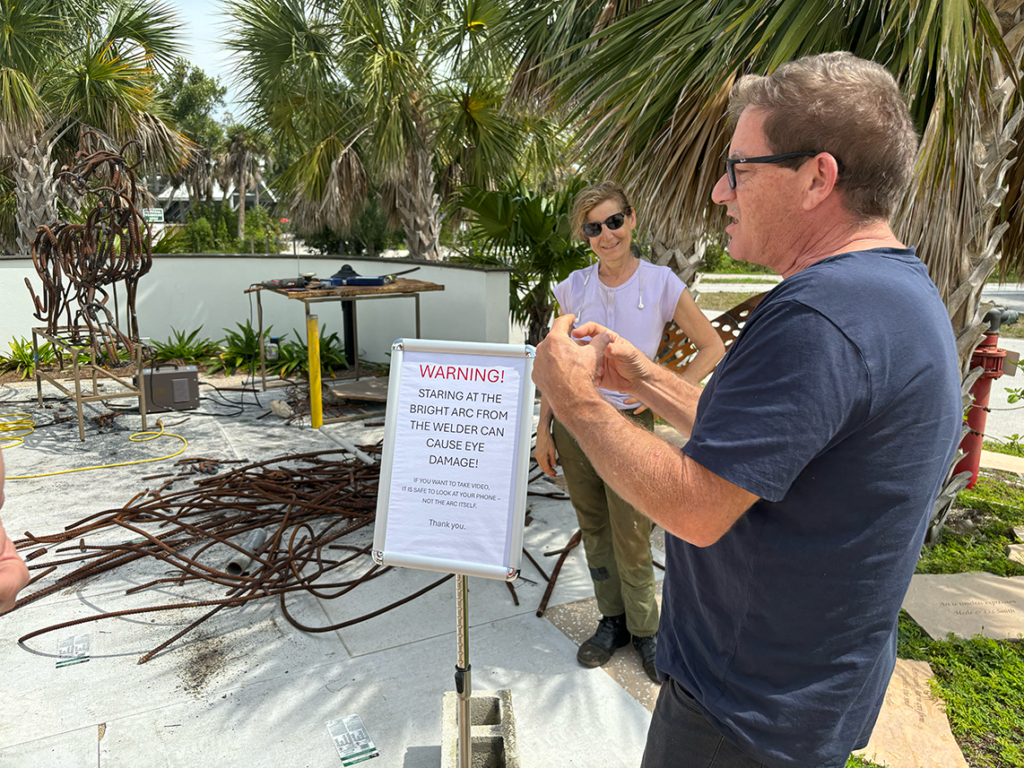

Although she pivoted away from STEM, she still uses science in her work. To create her sculptures, she welds pieces of metal together. One of the tools she uses is a torch that combines oxygen and acetylene gas by storing them in separate cylinders and combining them in the resulting flame. Acetylene is an odorless and extremely flammable gas. By adding oxygen to an acetylene flame, Klemperer raises the temperature of the flame, which allows her to cut a clean line through a block or rod of metal. To get the correct temperature, she adjusts the pressure of each of the gasses. For example, to cut steel, she can set the acetylene to seven psi (pounds per square inch) and the oxygen to 40 psi. (Pounds per square inch indicate that for every square inch of area, the gas applies a certain number of pounds of force.)

Another tool she uses, more frequently than the torch, is an electric arc welder. Electricity, rather than gas, powers arc welders: they use electric sparks rather than flame to melt metal. To create an arc, one cable coming out of the machine ends in a “work clamp” that clamps onto whatever piece of metal Klemperer is working with. The other cable ends in a gun with steel wire that sends out electricity.

Together with the metal, these lines form an electric circuit. If Klemperer simply touches the end of the wire in the gun to the metal, the metal vibrates with conducting electrical charge and nothing melts. But by holding the gun a fraction of an inch away from the metal, she creates an arc that flies from the gun to the metal. This arc is hotter than the 6,000 degree flame from the torch, but it’s far more concentrated so less energy and heat are wasted.

Klemperer’s background in chemistry played a big part in her understanding of metal’s composition as she learned to work with different types of metal alloys (iron, steel, stainless steel, cast iron, and bronze). Not only does she engage with physics and chemistry through the tools she uses to form the sculptures, but she draws on biology for the subjects of her work itself. Thus, she creates a study of animals in motion.

Her love of animals pervades Klemperer’s entire artistic process. She acquires most of her materials from scrap yards and construction sites, reducing the environmental impact of her work. Plus, her sculptures embody the way that animals move. She does this by viewing her sculpting as “a kind of three-dimensional gesture drawing.” In the art world, “gesture drawing“ refers to adding lines that indicate movement or show the connection between different objects or parts of the body.

For Klemperer, capturing the “gesture” of an animal lets her represent them moving as they would if they were a living being. This means that it looks like the cheetahs are poised to pounce, the wolves are howling, and the elk are swimming through water … even though they are all made entirely from once-unwanted pieces of metal.

Science makes Klemperer’s art possible. Without it, not only would her welding tools not have been invented, but she wouldn’t understand the nuances of how to use them. It also teaches her how animals look and behave so that she can capture their wild beauty. As Klemperer turned to art over science, her parents supported her fully and took endless pride in her work. If you want to succeed as an artist, you don’t need a degree in biochemistry from Harvard, but you do need to have an appreciation for how the world works and a desire to understand it. And that’s all science really is.