Marek Bennett studied math, music, and astronomy in college. Now he uses what he learned in his work as a cartoonist.

Do you like to draw or to read graphic novels or comics? What do you draw? What are your favorite comics or graphic novels?

For Marek Bennett, writing algebraic proofs, composing songs, reviewing Civil War documents, and drawing cartoon rabbits require the same essential skill: creativity.

To understand how Bennett came to this conclusion, you need to know about his academic career at Brown University and how his childhood led him there. Before entering an Ivy League university, Marek was a boy who loved Star Wars.

He “was fascinated by the idea of people living their lives literally among the stars, moving from place to place among all these colorful planets & spaces. And then [he experienced] that first moment as a kid when you realize the starlight that we’re seeing is thousands/millions of years old…. That felt like such a revelation of a great cosmic riddle, or even a joke — Who wouldn’t want to look up into that mystery & figure out what’s going on out there?”

In school, Marek loved math and science for the reason that many students do: there’s one clear right answer on the homework assignment or test. You’re either right or wrong and there is no need to meddle in ambiguities. For him, the combination of mystery and clarity fueled his passion for STEM.

However, once Bennett started his time at college, he quickly realized that higher-level math doesn’t have the same certainty as high school math does.

He enjoyed working on mathematical proofs: “Coming up with proofs is such a creative process: it always … gave me the same feeling as composing a piece of music according to the rules of whatever makes it music.” It also reminded Bennett of “playing a chess game: it’s hard and then you realize something and things start falling into place.”

A mathematical proof is a way to prove whether a statement is true or false. For example, if x=y and x=1, then y=1. As straightforward as that may seem, the process sometimes leads to surprising results. Below is Bennett’s video explaining proofs.

Bennett didn’t start as a math major. At first, he was aiming for the stars. He was interested in astronomy and studied it for the first few years of school. However, he was never at the top of his class and struggled to keep up with his peers. That’s when he realized that he had already fulfilled half of the major requirements for the math department. Wanting to free his schedule to do a weekly comic strip for the school newspaper, he switched majors.

Bennett had also always been interested in music, so he took music classes throughout his college career. He focused on algorithmic music. Algorithms are sets of rules or processes, normally used by computers. Algorithms allowed Bennett to string together simple sounds to create new auditory experiences. When he was registering for classes for his senior year, he learned that he could get a music degree if he filled his last semester’s schedule with music classes. Bennett managed to transition from studying astronomy to music and math by following his interests and paying attention to the opportunities his school offered.

Surprisingly, there isn’t a clear career path for a music and math-loving comic artist. Bennett built his career through “trial and error.” In 2023, he released volume three of his nonfiction graphic novel series The Civil War Diaries of Freeman Colby, which portrays everyday life during the Civil War. Before starting the series, Bennett worked on several other social studies-based projects. The first was the graphic novel Slovakia: Fall in the Heart of Europe. Slovakia is about a rabbit traveling through Eastern Slovakia and is based on Bennett’s own experiences traveling through Eastern Europe — a trip that inspired him to rethink his ideas about storytelling.

Bennett also contributed to The Mostly Costly Journey: Stories of Migrant Farmworkers in Vermont, Drawn by New England Cartoonists. The book started as a series of pamphlets created for a free health clinic in Vermont that serves both undocumented workers and other uninsured people in the area. The goal of the pamphlets was to address the social isolation caused by their long working hours and the need for undocumented workers to hide away from the immigration police. The nurses at the clinic thought that by sharing their stories with each other through comics, the workers could feel less alone. The project took off. Soon, with the help of several Vermont nonprofits, including Vermont Folklife and a Kickstarter campaign, the pamphlets were combined into two books (one in Spanish, one in English) which serve to help the farmworkers and teach all Americans what the life of a migrant farmworker is like.

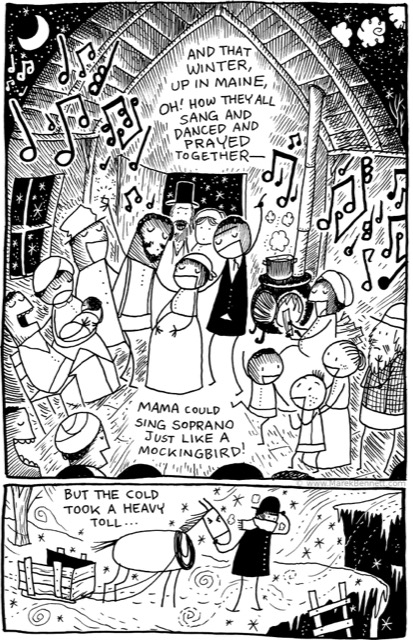

The success of that project led Bennett to collaborate with Vermont Folklife again when he contributed to the anthology Turner Family Stories: From Enslavement in Virginia to Freedom in Vermont. The book tells two stories from the life of Alec Turner, a formerly enslaved man who settled in Vermont in the 1800s. This project sparked Bennett’s interest in the Civil War and led him to write the Freeman Colby series.

While Bennett’s books seem to be a far cry from his mathematical roots, to him, they use a similar set of skills. To create a cohesive story of the past, Bennett has to draw from several sources: from historians’ work as well as from documents from the historical time period. But even with all of these resources, there are often gaps in the historical record that can span several months. When this happens, Bennett has to make logical deductions by combining information from different sources to figure out what happened.

For example, Union soldiers in one account said they marched through enemy territory in Virginia, knocking on farmhouse doors asking for a chicken, and finally got one. Bennett wanted to know how they got a chicken, but the account didn’t go into detail. However, he learned from another document that escaped enslaved people would travel through that area helping Union soldiers by showing them secret paths. Another historical account quoted an escaped enslaved woman saying, “The soldiers ate all my chickens but I did have one left.” All of this information combined led Bennett to the logical conclusion that the soldiers could have acquired the chicken from an enslaved person who wanted to help them.

Bennett says that this historical deduction process “really reminds [him] of how astronomers have put together these models of what’s going on in [a star that astronomers can’t even see.]…”

He explained that stars like these are “a point of light so far away. We only know its spectral lines and apparent luminosity, and we can tell its distance. From [its distance] we can tell how bright it really is and from that the temperature. From a few facts, you can start extrapolating a rich sense of what’s going on in that place. I’m really aware that when you’re talking about that star out there, you’re talking about something as it existed hundreds of millions or billions of years ago. You’re … talking about the past.”

Like in the natural sciences, historical research also needs testable hypotheses. After combining information from various sources to craft a complete narrative about what may have happened, Bennett then goes in search of records that confirm that something like that did actually occur.

In addition to his books, Bennett leads comic workshops for students throughout New England. He believes comics can engage a broader range of students who learn in different ways by drawing on all of the different modes of intelligence.

He’s also recently turned his cartooning skills back towards STEM subjects. He received a grant from the United States Department of Agriculture to create comics about how lead pollution impacts the life cycles of loons.

The humanities and STEM are often posed as nemeses (rivals). Some people assume that you’re either creative OR good at math. You either obsess over chemistry sets OR paint sets. You either read history books OR the newest scientific literature. But many people love both STEM and the humanities. Bennett wouldn’t be as good at understanding history or creating music without his STEM background. He also wouldn’t be as good at communicating STEM ideas without his artistic bent.

During the height of the COVID pandemic, medical professionals and scientists were held up as heroes, and people often commented on how more people should pursue these subjects because they are so valuable to society. But those scientists, doctors, and nurses depended on the TV shows, music, books, and movies created by artists to emotionally survive that traumatic time. Science and art need each other. Science teaches us how the world works. Art asks us what the world means.

So if you’re a history-loving, comics-drawing musician who wants to study astronomy and math, don’t worry. Marek Bennett’s career proves that there is a path for you.