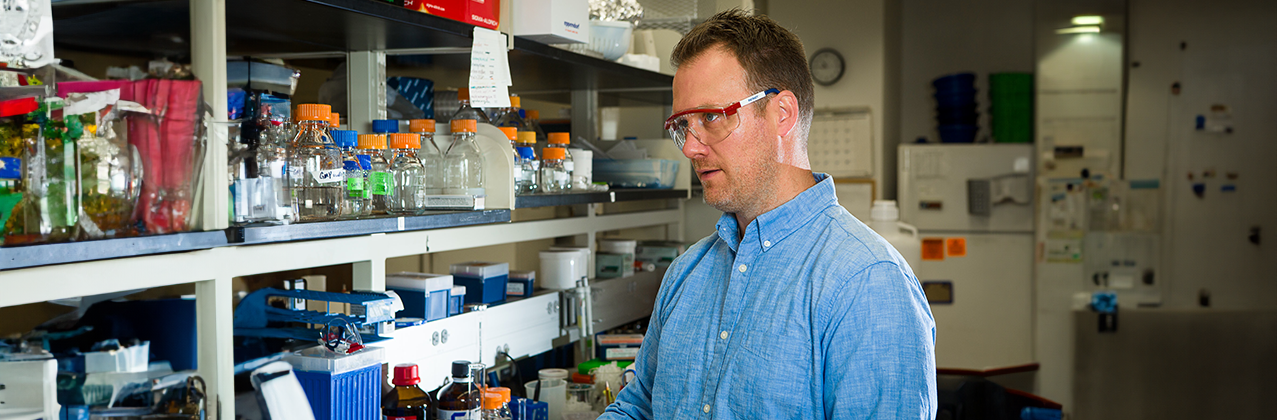

You might think of microbes as “germs”: tiny organisms that make people sick. But our bodies contain ten times more microbes than cells of our own. Many of those microorganisms in our bodies and other microbes living in the soil, air, and water of our planet help keep us healthy. Environmental microbiologist Luke A. Moe studies ways microbes make certain chemicals less dangerous and how they help plants obtain nutrients from the soil.

When oil spills, whether on land or into water, it can harm the plants and animals that live near the spill. Scientists in many fields work to prevent oil from spilling and, when it does spill, to investigate its effects and find ways of making it less destructive. While working on his Ph.D. in biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin, Moe researched the ways certain tiny forms of life digest toxic chemicals. He looked at enzymes within microbes which break down chemicals like toluene, using them as an energy source.

Toluene improves gasoline by raising its octane rating. Because it’s a solvent, it helps dissolve other materials, so companies add it to paint, adhesives, nail polish, and other products. But when people or other organisms breathe too much of it, toluene can cause serious health problems.

In Wisconsin, Moe explored the ways Pseudomonas mendocina, a type of bacteria, breaks down the carbon skeleton of toluene, turning it into harmless molecules the microbe uses to make amino acids, DNA, etc. Understanding more about how these microbes work may help us clean up toluene and other chemicals that spill or leak into different environments.

Growing up on a farm in Washington state, Luke spent a lot of time outdoors, often taking things he would find there apart and putting them back together. “Being exposed to nature was one of the key drivers, but it wasn’t until college that I figured out that I wanted to be a scientist.” In college, Moe learned about the “enormous capacity of microbes to impact everyday life.” Classes in biochemistry and microbiology taught him that microorganisms are everywhere: out in nature, in our food, and in the human body. While the science he studied before college did not give him much of a sense of the usefulness of chemistry and biology (“not the optimal way of presenting the material”), now he could see how very useful they can be.

Just as we form symbiotic relationships with microbes, giving them a place to live in exchange for their help digesting our food and doing other things, plants form similar relationships. Working at the University of Kentucky, in Lexington, Moe and his colleagues examine the different types of microbes that live around the roots of plants. Plants release chemicals from their roots, sending messages that attract the microbes they find helpful and repel harmful ones. Basically, there’s a secret “chemical language at the root surface,” a code that Moe is cracking, helping plants communicate with bacteria. Those bacteria can help them absorb nutrients from the soil. Plants from the family Fabaceae (legumes, such as soy beans and peanuts) protect the bacteria by growing nodules around them. Knowing the genetics and other chemical components of these activites can help farmers grow species of legumes that will fix nitrogen in the soil efficiently, thanks to their ability to work well with the microorganisms in their rhizospheres (the area around their roots).