Behavioral Ecologist Jeanne Altmann the baboons of Africa.

What’s the coolest animal you have seen?

How can a scientist get close enough to a group of animals to observe and record their behaviors but stay far enough away to allow them to feel safe? How does she make sure that the animals don’t become so accustomed to her presence that they change their behavior, developing a close relationship with the scientist watching them?

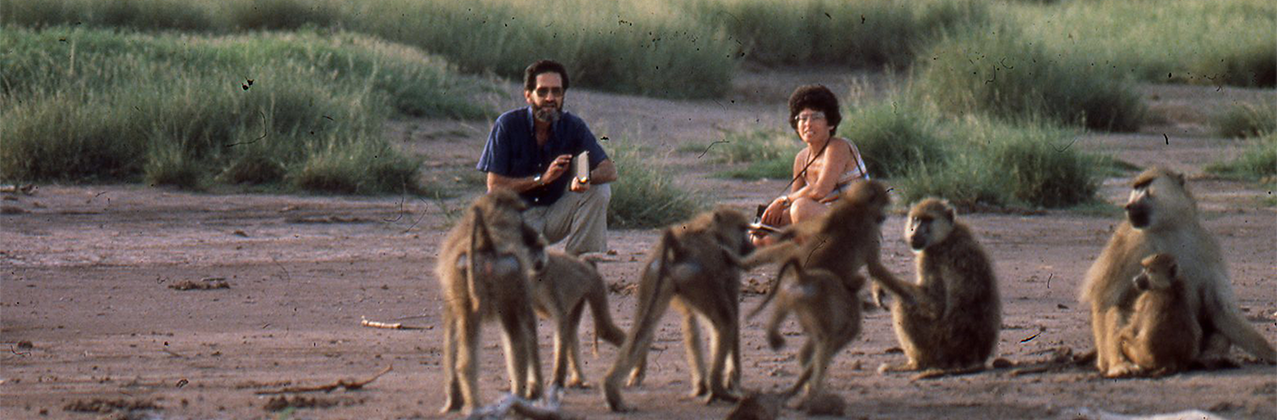

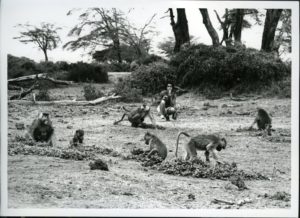

These questions become especially important when a scientist like Behavioral Ecologist Jeanne Altmann studies animals raising infants. “I always tried to stay at a distance that would not discourage the mothers’ interactions with the most sensitive individuals in the group,” Altmann says in Baboon Mothers and Infants, a book that advanced our understanding of baboon behavior and the relationships between baboons and their environment.

Working with yellow baboons (Papio cynocephalus) in Kenya’s Ambelosi National Park, Altmann “stayed with the group from 0730 or 0800 in the morning until 1730 or 1800 in the evening. The animals were never fed, and I tried to minimize my effect on them.” She and her colleagues collected information about the ways baboon mothers spend their time, their diets, and the food their infants eat. They studied the relationships adult females form with other adults and young baboons, the distances growing baboons travel from their mothers, and the changes that happen as infants grow into independent adults.

“Baboon parenting is a lot like human parenting,” says Altmann. In her decades spent watching and writing about the baboons of Africa, the primates taught her lessons that apply just as well to raising human children. “Being overprotective is not the best,” she says. The important things for children? “Getting enough food, protecting them from dangers, and providing an environment in which they learn to protect themselves.”

Altmann, now Eugene Higgins Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Emeritus and Senior Scholar at Princeton University, is a pioneer in science, a woman who became a renowned researcher and professor after she raised her own children. “My career is historical,” she says.

“I don’t have a clue” how I became a scientist, she says, as she had few female role models to inspire her to do that. Born in New York City, she was raised in the suburbs of Washington DC by parents who were very supportive of education in general, though not of careers for women. And they were anything but the outdoor type (“My mother was allergic to any type of mammal,” she remembers).

However, like her father, Jeanne always loved puzzles: mental puzzles, jigsaw puzzles, and three-dimensional puzzles as well. And she enjoyed math. “I think my sixth grade teacher had taught math around the world in army bases and then came and taught school. My mother taught school. So that was my thought: “Well, I can teach math around the world and so I can get the heck out of here if I teach math.”

She began college as a math major at UCLA when her family moved to Southern California. Soon, she met her future husband, biologist Stuart Altmann, and they moved from the West Coast to Boston, where Altmann did computer programming for a neurobiologist and became one of 10 female undergraduates at MIT (the Massachusetts Institute of Technology). Her work with computers at this time gave her “a taste of data analysis and programming,” which helped shape the rigorous approach she would take to her work as a behavioral ecologist.

After a year in Boston, the Altmanns went on to Edmonton, where Stuart had won an appointment to the Biology faculty at the University of Alberta and Jeanne finished her B.A. in Mathematics. Though none were on the faculty, many wives of male biology professors had their own PhDs in biology and helped run the labs. They were hampered by rules and regulations that prevented them from working in the same departments as their husbands, even though they were trained in those fields.

“Observational Study of Behavior Sampling Methods,” her work revolutionized the study of animal behavior in the wild.

Drawing upon her experiences studying math, working in data analysis, and assisting Stuart with primate observations in Kenya, Altmann explained how scientists studying animal behavior could gather unbiased samples and analyze the data they collected in different ways. As Altmann explains, “I especially used focal animal sampling,” a method that involves watching an animal for a certain amount of time and recording everything s/he does. That way, “even shy animals got equal time and all animals were observed equally, not just the loudest or pushiest.” (Math4Science Animal Behaviorist H. Jane Brockmann confirms that Altmann’s article was “seminal,” explaining to biologists and zoologists studying animal behavior how to collect and analyze data.)

After Atlanta, Altmann ended up at the University of Chicago, where she did doctoral work, focusing on baboon behavior. “I was interested in the importance of family relationships for survival and reproduction,” she says. Again, however, she encountered those who told her she was pointed in the wrong direction. “At the time, [this] was considered a soft ‘woman’s’ topic.” These critics believed, incorrectly, that males were the important members of any species, that baboon research had been played out, and that there was nothing left to learn. But Altmann would soon discover much more about the relationships in baboon families and communities.

Fortunately, her husband Stuart “was much more feminist than many of the men his age–he and the kids got good at making dinner.” And when her research required her to spend time in Kenya, observing baboons in their habitat, Altmann’s family moved to rural Africa, where she and Stuart “tent-schooled” their children.

In Africa, Altmann used her rigorous sampling methods to record the behavior of all baboons, including the females, who, up until that time, had been largely ignored. Choosing baboons randomly in order to assure an unbiased selection of behavior to study, Altmann learned that female baboons, like their male counterparts, live in a social structure that is ordered in a strictly hierarchical manner. Low-status female baboons often find their young offspring kidnapped by higher-status females! This happens most often to first-time mothers, who have not yet learned to keep their children close when they go about their daily routine, which mostly includes foraging across the savanna for food and caring for their babies.

Another interesting finding, and one that supports the notion of female social hierarchies, is that a few females, born into low status, manage to climb the social ladder by befriending–mostly by grooming–the popular girls.

Though female parents most often take care of baby baboons, Altmann and her colleagues have used genetics to discover evidence that male baboons recognize their own children. When danger appears (e.g. when a lion attacks or a mother dies), baboon fathers step in to provide help.

Altmann has mentored scores of students, from high schoolers to postdocs. She especially enjoys guiding young women into science careers, and is proud of her project’s long-standing policy of working closely with Kenyan scientists and technicians in order to benefit from their local knowledge and to provide training and employment opportunities to those who live near the baboons’ habitat. Now that she is a professor Emeritus, Altmann still travels to Kenya to continue the work she began decades ago. She is also involved in the curation of her project’s records, much of which is now electronically on the web for use by team members at Duke University and University of Notre Dame and elsewhere around the world .

“It’s very important to me that our work last into the next generation and beyond. We’re now on our eighth generation of baboons, and our third generation of researchers. After 45 years of observation, there is still so much we can learn.”

[1] Altmann, Baboons Mothers and Infants (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980), 22.

[2] 5:30 p.m. or 6:00 p.m.

[3] Altmann, 28