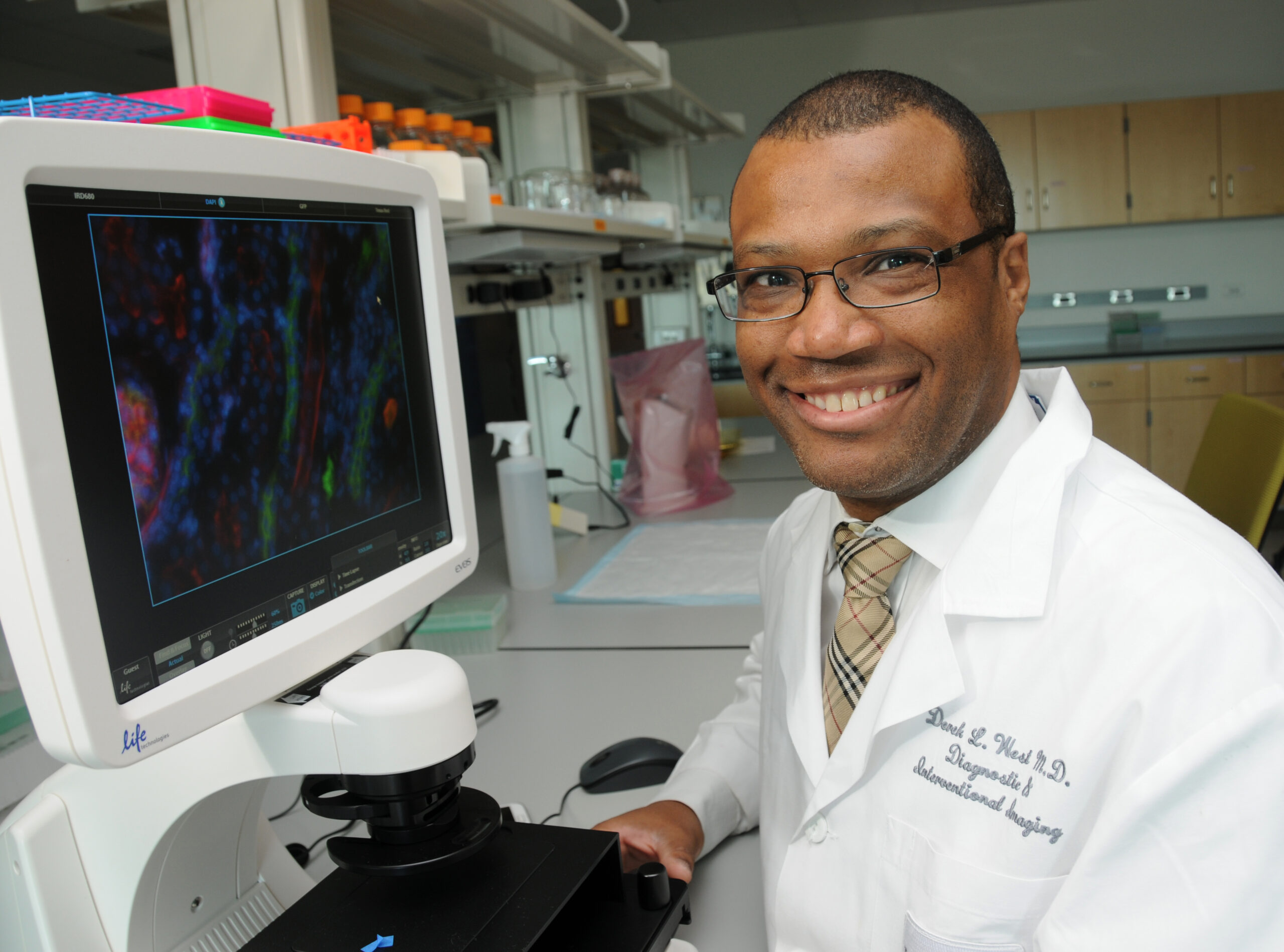

Bioengineer Derek West particles of gold so small that you can’t see them without special tools to help find ways to kill cancer cells.

What illnesses scare you most? Why?

Bioengineer Derek West works with tiny particles of gold, particles so small that you can’t see them. A meter is a bit longer than a yard. People do not grow to be as much as two meters tall (but most adults are taller than one meter). If you look at a ruler that measures metric length, it will probably be divided into centimeters. There are 100 centimeters in a meter. On your ruler, each centimeter is divided into 10 very small lengths, called millimeters. (How many millimeters are there in a meter?) Imagine dividing each millimeter into a million tiny pieces. Each of those pieces would be one nanometer long.

West takes gold that’s about a nanometer in diameter, small enough to fit into a cell but large enough to be detected. The particles of gold he uses absorb light, allowing him to heat them up with a laser. When he attaches these particles to an antibody that recognizes cancer cells, he can send them into the cells of a tumor, heat them up, and destroy the cancer cells without damaging the normal cells around them.

Working with such small tools also helps West and his colleagues deliver advanced forms of chemotherapy. They use catheters to send chemicals directly to the blood supply for a tumor. Because the chemicals are focused right on the area affected by the cancer and not on the rest of the patient’s body, they can be more concentrated than chemotherapy delivered by an IV.

West uses electricity to make tiny holes in pancreatic cancer cells, holes that nanoparticles can enter. He tests the effects of these holes on the cells in test tubes, in mice, and, finally, in human beings.

Because West’s father was a doctor, he himself planned to become an engineer. He studied engineering in college, “but it didn’t hit me right.” As he moved from engineering into science, West found himself particularly enjoying classes in biochemistry and organic chemistry. “I enjoyed learning about the Krebs cycle and that sort of thing; it came naturally to me.” When a friend convinced him to take the MCAT, the exam students take to be accepted to medical school, West “got a high enough score that the dean told me ‘you have to go to medical school'” … and he did.

After becoming a doctor, West worked in hospitals and in a private practice. As an interventional radiologist, he used X-rays, ultrasound, MRIs, and other tools to find, test, and remove cancerous tumors from his patients. But he never lost the desire to do experiments: West wanted to use the science and engineering he had learned in school to do the research necessary to improve the treatments available to his patients.

To go into research, “you need someone to mentor you.” Radiology Professor Reed Omary encouraged West to do postdoctoral work in cancer research and nanotechnology at Northwestern University, helping him start down the path that would lead to working with those tiny particles of gold. Now West works on paying that forward. “I do some mentoring for African American students trying to get into medicine. I remind them that they have to engage in the game.” Remembering his own struggle to get good grades in college, West advises students preparing for exams to work together, using practice tests and study groups to help them succeed. And he’s part of a diversification task force at the American College of Radiology, because he recognizes the importance of providing students with mentors in whom they can see themselves. “There are unique circumstances that I deal with as an African American.” And West sees a need to recruit more women into his field. “There aren’t many women who can mentor someone coming up” in medical research.

The first person Derek remembers becoming his mentor was a high school math teacher, Hannah Goldschmidt, “by far my best teacher.” She was “the first teacher I felt actually cared whether or not I learned the material.” When Goldschmidt taught math, “she conveyed that these were things that you have to learn for life, not just for the test and not just for the grade.”

West is grateful that he remembers as much of the trigonometry, calculus, and probability he studied in the past as he does. Understanding the math biostatisticians use “gives you a leg up when you’re doing clinical studies. You have to understand what they’re arguing about; otherwise you’re out of it.”

Thanks to the successes West and his colleagues are having in their labs, more and better treatments for cancer are becoming available.