Every spring and fall, millions of birds migrate long distances across North America: song sparrows, oven-birds, common yellowthroats, black-and-white warblers. Some, like the black-poll warblers, venture as far away as South America, and as self-taught ornithologist Laura Gooch found, many may traverse your own backyard.

Gooch wasn’t always an ornithologist. Trained as a civil engineer, she has traveled across the United States, helping improve systems that make our environment as safe and productive as possible.

Texas, like many states, has limited water available for people to use at home and at work, so there are often disputes about who is allowed to own this scarce resource. Laws in this state say that anyone who has a river or stream on his or her land is eligible for water rights. And once these rights are granted, they are final: no one can claim rights who does not already have them.

The Brazos River Authority built the Morris Sheppard Dam on the river from 1938 to 1941, creating the Possum Kingdom Reservoir. It cost $8,500,000 to build the dam, which helps engineers provide water to homes and businesses in that area of Texas, prevent floods, and produce electricity. It also caused a dispute that Gooch, as an engineer working in the water resource planning department of the Fort Worth consulting firm of Freese and Nichols, would help to solve, using her civil engineering skills.

A small but steady leak through the dam’s turbines created a habitat for fish in the river downstream. Gooch and her colleagues had to consider the fate of these fish and the recreational fishermen in that area when deciding whether to fix the leak. Texas’s Parks and Wildlife Department took the side of the fish and fishermen and the Brazos River Authority pushed to fix the dam.

Gooch and her colleagues investigated the impacts of different alternatives on the river, the Possum Kingdom lake, and the people and animals around them. They investigated the past and present flow of the river, using units of measurement common to American water resource engineering. These include acre-feet (the amount of water that would cover an acre of land at a depth of one foot) and cubic feet per second, a measure of the rate of flow. In the end, they found a solution that repaired the dam and also pleased the fishermen. The dam’s turbines were replaced and the leak was fixed. Water was released regularly to protect the fish living downstream.

When Gooch moved to Cleveland, Ohio, she decided to change the focus of her work. In her new home, water was plentiful thanks to Lake Erie, so water resource engineering seemed less exciting. But local industries produced dangerous waste and the Superfund Law of 1980 promised to keep civil and environmental engineers like Gooch busy cleaning up contaminated areas.

At one point during the years she worked with the hazardous waste investigation and remediation department at Engineering Science in Cleveland, Gooch helped design the clean-up of the first completed Superfund site in Ohio. Over the years, a greenhouse operator in a rural area near Cleveland had collected waste oil from industry sites to heat his greenhouses. At first, he paid companies operating local industries for their waste oil. Then, he discovered that the companies would pay him to take the oil and dispose of it. He dumped some of this waste oil, which contained toxins such as PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), onto his property and he gave some of it to other people, who used it to control dust on roads and school fields, allowing the toxins to spread farther.

When the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) became aware of the situation, the property was designated as a Superfund clean-up site.

To get the clean-up started, the remediation team brought in an air monitoring system to detect any toxins that might be released when soil was incinerated (burned) and to make sure that air leaving the site was safe.

The team used mathematical models to keep poisonous chemicals from passing into the groundwater and capped the site to keep toxins away from water flowing through the property when it rained. This cap had many layers, including a water-proof polyethylene membrane with synthetic fabric, soil, and clay over that to help drain rain and other water away.

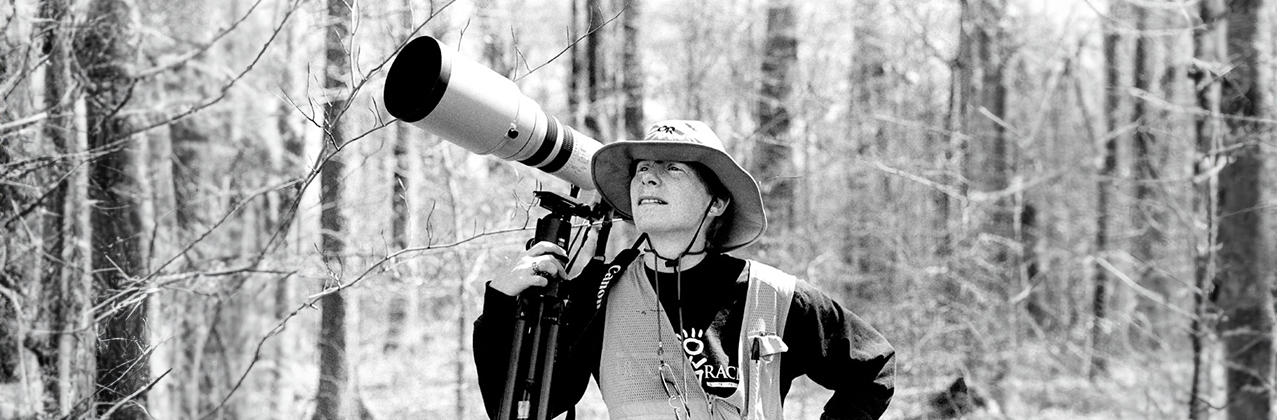

After fifteen years of civil engineering, providing Texans with water and Ohioans with an environment safer from toxic waste, Gooch took a leave of absence to pursue her interest in birds, which grew into a strong fascination.

At first, she took pictures of birds. Soon, however, she began to join bird-banding efforts. Conservationists catch birds in nets, check their body mass, and record their wing-length, age, sex, and species. They fit each bird with a band containing a 9-digit number before releasing it. The data they gather is entered into a USGS (United States Geological Survey) database, helping scientists monitor bird species. If a banded bird is recaptured, the band it’s wearing provides valuable information about the bird’s age and where it has been.

Especially fascinated by bird migration, Gooch began to monitor birds’ nighttime movement at her house, using sky-pointing microphones and recording into her computer. Each day, Gooch checks her computer, noting as many as 1,000 or sometimes even 4,000 calls from birds that flew overhead the night before. She identifies each bird’s species with a spectrogram – an image on her computer that represents sounds visually. Warbler calls are fast, with high frequencies, while the sounds of thrushes are slower, with lower frequencies.

In addition to monitoring night flight call, Gooch and her husband make high quality recordings of the songs of individual birds, which can be used by researchers to study bird communication and behavior. They use their own designs of parabolic microphones, similar to those used in sports games, and exponential horn microphones, which look like megaphones, to record bird song in Ohio and other parts of the United States. Their recordings are archived at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library of Sound.

Growing up in Texas, Laura was surrounded by science. Her father was a water resource engineer, and while he did not push for his children to follow his path, every member of Laura’s family shared his interest in science. Laura liked building model cars as a child (and still enjoys building model planes), but was less encouraged than her brothers to pursue this interest. As a teenager, she worked in her father’s office as a keypunch operator, punching holes in computer data cards to track building energy use at an army base.

Gooch has used math and science to work with water, toxic waste, and birds. Her achievements and those of other civil engineers help the birds she studies now (and the rest of us) find clean water, food, and shelter.